Servicios Postales del Peru (Serpost)--not your friend

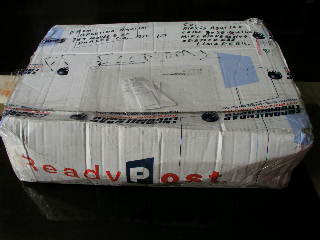

I just returned from picking up a package from my mom which was being held at the Peruvian post office customs department. The innocent-looking notice came yesterday saying that I needed to pick up a package. Being the national post office, I thought it would be at a nearby location. Well, after a 40 minute taxi ride I finally arrived to the postal annex where my 17 lb.-package of books was being sequestered. A guard at the entrance asked for the notice and my ID. Then he directed me to window #1 where I filled out some paper work after showing my passport again. I took that piece of paper to window #2 where a nice lady took it and gave me a ticket with the number 09. Number 94 was showing on the screen. The numbers advanced painfully slowly and seemed to completely stop when they reached 01. I went up to a window where they were delivering packages to inquire why the numbers had stopped and was directed to another window . As I waited in line at this other window I noticed 02 was now on the screen. "Ok, I thought it can't be much longer, at least the numbers are moving again". So, I sat down to do a crossword puzzle.

After a while, 09 finally came up. I went to window #3 where after showing my passport and handing in some paperwork I was told to wait "a little while" for my name to be called. I sat down again wondering why all the Serpost employees looked so busy behind the counters while all the clients where just sitting around holding on to their ticketed numbers. What where they looking at so intensely on their computer screens? Why did they keep shuffling through paper files? After another while, a pregnant german woman, who along with her Peruvian husband had been there longer than me, grew impatient and started complaining outloud about the Peruvian postal system, how this was the most ridiculuos postal office she had ever seen and how this would never happen in Germany. I thought "Welcome to Peru, welcome to Latin America, welcome to any place where bureacracy still serves to keep people employed". I had seen my package. I saw it behind window #3 and was able to read my mother's name on it. Only a glass window and a few steps kept me from it. I started fantasizing: what if I ran in (there was a small access door), grabbed my package and ran for life. Then I remember the security guard outside. That's why they had a security guard at the gate, I thought, to keep people from snapping and stealing their own packages. It had been much more than "a little while" and my name wasn't being called, nor was the german woman's, nor was anybody's. The german woman went to window #4 and after some untelligible haggling she came out holding a piece of paper and shouting "yoo-hoo!" with evident glee. Ok, I thought, if the german woman did it, why can't I? I went to window #4 where a small crowd had gathered after seeing the success of the german woman. After waiting in line, showing my passport, and sigining a piece of paper, I was handed the final piece of paper that confirmed that I had sufficiently suffered Serpost and had earned the right to receive my package. I was told to go to window #5.

At window #5 I waited in line behind the german woman. Then an elderly woman arrived and waited behind me. After a while, she grew impatient and moved to the front of the line. Her granddaughter called her to return to the back of the line, but she paid no attention. I told the german woman, "wasn't she behind me? what's she doing upfront?" Then an argentine woman who was now behind me said "what a conchuda she is". The german woman tapped the elderly woman's shoulder and told her to move back into the line. The elderly lady mumbled something about being in a hurry and something about her grandaughter I couldn't understand. Then, the argentine woman exploded and began shouting at the elderly woman telling her that she had been there since eight in the morning (it was now around 12:30 pm), that everyone had other things to do, and that she had kids to go feed. The elderly lady told her to be quiet, which incensed the argentine woman even more and shouted "No me joda, it's my democratic right to say whatever I goddamn please!" Fortunately, the elderly woman agreed to return to the line before things got out of hand. Also fortunately, because my package contained only books, it was exonerated from paying custom taxes. With my package in hand I hurried out of the postal annex--not before having to identify myself with the security guard again--to hail down a cab for the long ride back home. After I told my story to the porter at our building, he wisely advised me: "next time use a private carrier".